Using Evolutionary Algorithms for the CVRP

Context

Tweaking the search heuristic based on benchmark data is a necessary evil when building and testing an OR model intended for production. But this approach has a problem: we are able to beat benchmarks but are not able to consistently get acceptable results in production, where the input data can vary for each run. One solution is to train the OR model in more benchmarks, but it is expensive for businesses to create the right benchmarks and to verify results when there’s a lot of variation possible in the data, or they are not sure of what variation can potentially happen, or the amount of work that goes into building the benchmark is high.

Does a solution exist that can adapt to any data input as long as the fundamentals it is built on are sound?

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) — when they work well — may be an answer. We decide the chromosome, mating and mutation methods, and let the EA “evolve” into a good solution. Unlike procedural heuristics (“if a happens, do b”), we have no control over how the EA evolves. This is both a weakness and a strength: a weakness because it might miss on obvious improvements (worse convergence), but a strength because it is agnostic to the state of the solution and relies purely on the evolutionary mechanism to improve results (more robust, less dependent on problem characteristics). Thus, for example, an EA might perform worse than a MIP on a linear problem, but can work well on a non-linear problem whereas an approach with a MIP at its core will need a lot of heuristics around it.

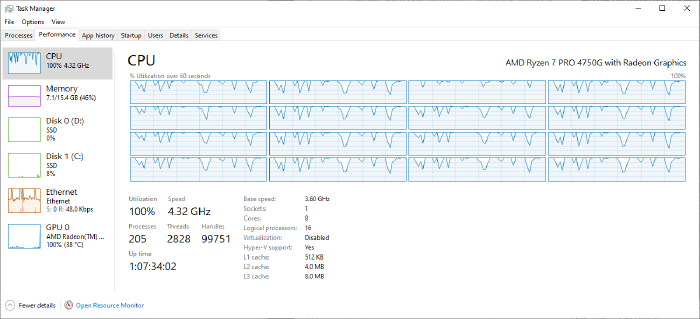

EAs have been around for a very long time but have not gained much traction, because their weakness has proved to be a bigger factor in the face of more precise analytical techniques. However, as hardware has improved in the last 5 years (and has enabled us to use AI and machine learning in unforeseen ways), I believe EAs may be able to leverage hardware to address their weakness and might be a viable solution method once more.

The DEAP framework

I started looking at EAs in my previous job, where I wanted to use it to find the KPI weights for the optimizer (perhaps a topic for a different post). I started looking at how I could evaluate what EA could do for me using off-the-shelf (and free) libraries. I found DEAP through this book and was able to get started quickly.

Note that when I say EA, I really mean Genetic Algorithms, and not one of the myriad other approaches (one of the swam intelligence approaches like Ant Colony optimization, for example).

The problem I picked was one I was familiar with: the Solomon benchmarks. These problems are well researched and have near-optimal (or optimal) solutions published. Getting close to these results would tell me that EAs are worth considering as a solution approach.

One last thing I did was to buy a desktop (AMD Ryzen 4750G with 8 cores at 3.6-4.4 GHz), as my 2013 MacBook Air with 1.3 GHz processor was not going to cut it.

Results

I got close to some (but not all) of the best known results.

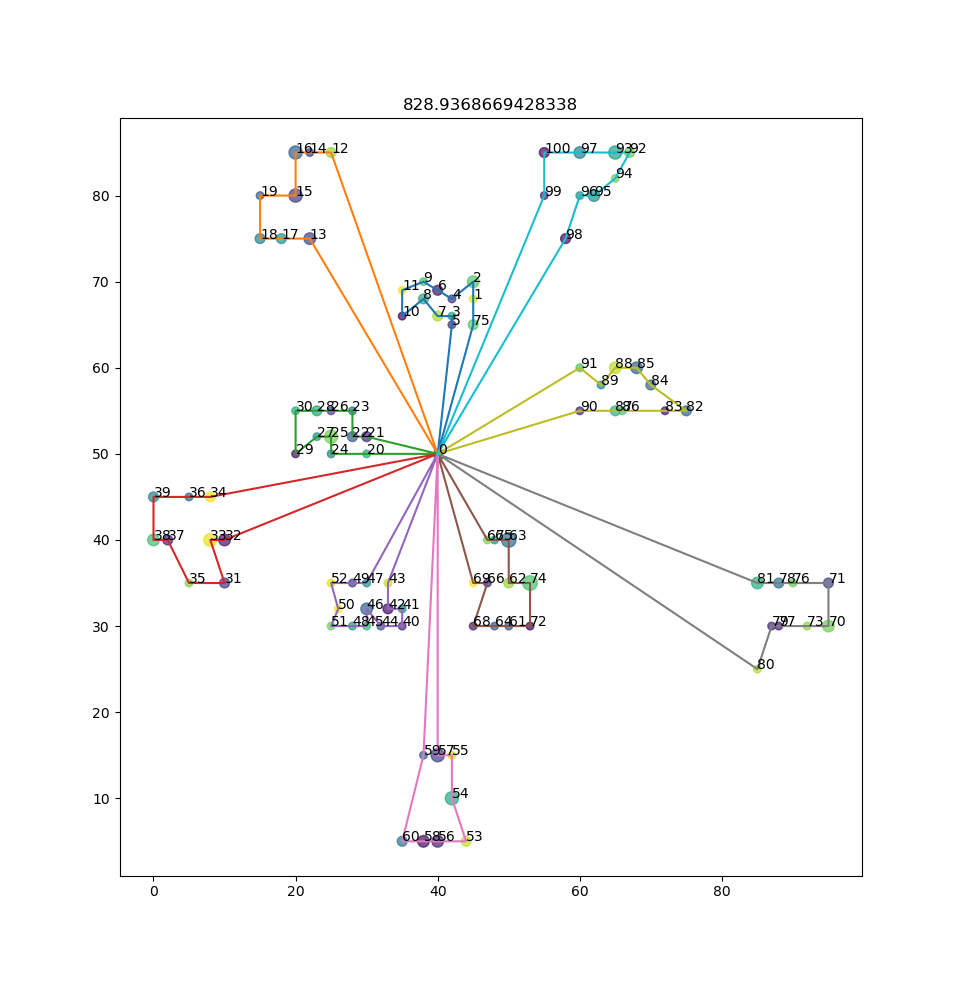

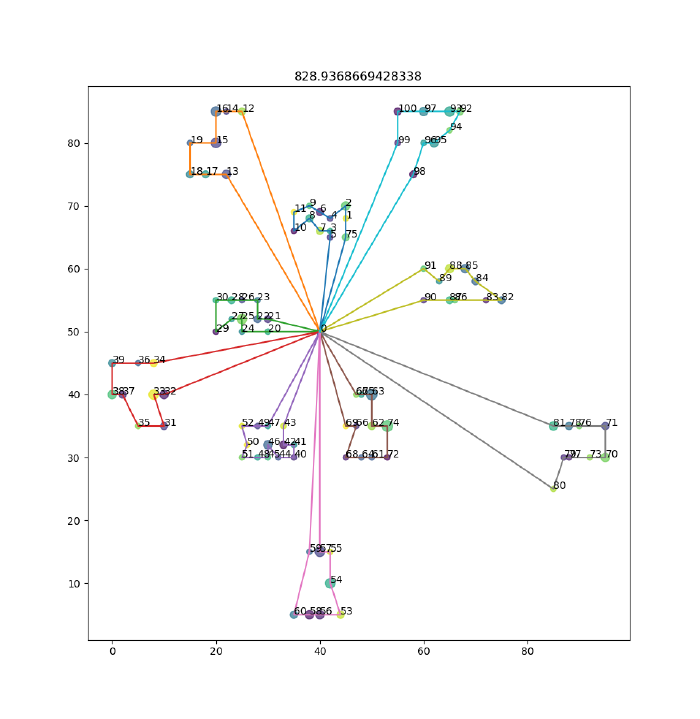

Result for C101: matched the best known result of 828.94

Result for R101: best result is 1650 (4% gap)

Result for RC105: best result is not even close (1377.11)

I worked on this for about 5 weeks from Feb 20 to March 30, for around 6 - 8 hours a week. Given the (lack of) effort I put in, I would call this a success.

If I had the opportunity to do so, I would implement a faster and more robust sub optimizer (in say Go or C++), perhaps using LKH. I had other ideas I wanted to try before I wrote this (I wanted to let the EA do sequencing as well) but I decided to close the loop and move on.

Code repository:

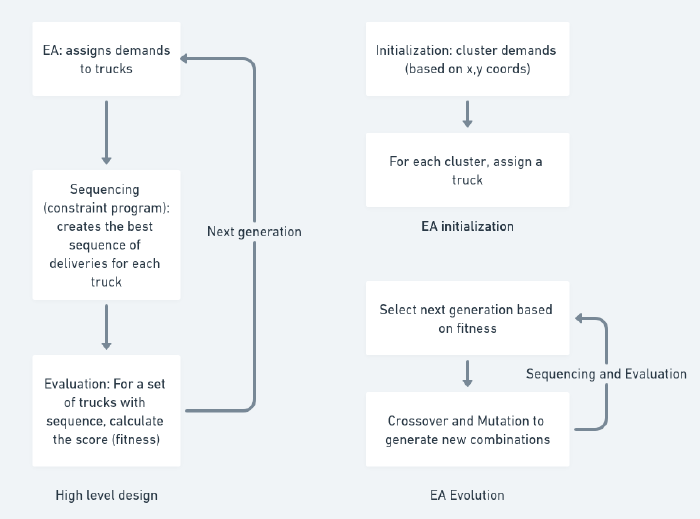

High Level Design

This is the design that worked best for me. It’s not the first design I came up with, and it isn’t the best one. More on this later.

I used EA to assign deliveries to trucks and a sub-optimizer to sequence deliveries, given the set of locations assigned by the EA. In this case I used a constraint program (ORTools CP-SAT solver) to do the sequencing.

Why the CP-SAT solver and not the graph solver? Because I wanted to allow for infeasible solutions (with a big penalty). I wanted every chromosome to be a ‘valid’ one, and to let it evolve naturally to a good solution from infeasible ones. The graph solver would have not allowed me the same flexibility as the CP optimizer.

The chromosome

Each gene in the chromosome can take values in the domain [0 - N), where N is the max number of trucks. Let’s say we have 10 locations (and 1 depot) and 2 trucks. One chromosome might look like:

0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1

In this chromosome, truck 0 covers the first 4 locations and truck 1 covers the last 6.

Sequencing

Sequencing focuses on one truck at a time. For the above example, the sequencing would run for truck 0 with locations 1 to 4 (assume 0 is the depot).

The sequencing optimizer would consider the following aspects:

- The time windows for the locations (penalizes lateness)

- The total distance driven

The sequencing optimizer assumes there’s no limit on how long a truck has to wait if it arrives before the window starts at a location.

Note that we can do nothing about the load at this stage, because that depends on the allocation of demands to trucks done in the chromosome. The load will be calculated as part of the evaluation to give the fitness of the chromosome.

Evaluation

Evaluation is straightforward:

- A penalty for every second that a truck is late to arrive at a location

- A penalty for the excess load in a truck

- Unit distance covered by the truck

We sum up the scores for each truck to get the final fitness score of the chromosome.

Evolution

With the chromosome designed the way it has been, crossover and mutation become quite simple, and every chromosome has a meaning (although it might violate load or time window constraints, for which it would be penalized).

For my tests, I chose quite simply: a two-point crossover and mutation that draws from a uniform distribution. More complex crossover and mutation methods in the DEAP library didn’t work quite as well (and I didn’t bother to investigate why).

The author of the DEAP book I referred to earlier had introduced a tweak called elitism where the best candidates in the previous generation were carried forward to the next generation unchanged. I found this to be invaluable in converging fast.

Performance considerations

Sequencing

With EAs, the evaluation of chromosomes has to be very fast in order to be able to explore more chromosomes and do more iterations. With the design I chose, the sequencing sub-optimizer was going to be the bottleneck of the solution.

With a constraint programming solver, performance comes down to

- How I can reduce domains faster

- How can I cause a constraint violation to happen earlier in the branching

These are related: a constraint is violated when a variable has no values left in its domain. Thus it sometimes helps to add redundant constraints which cumulatively reduce the domain of variables faster than if we were defining a single well-constructed constraint (like I would have done if this were a linear program, for example).

For the CP-SAT solver, this is what worked best for me:

- Like any TSP-like problem, I had arcs between every pair of locations. But I changed the meaning of the arc from

a->bmeans that “bis the next location aftera” to simply “acomes beforeb”. Why? Because this allowed my time and distance calculation atbto be faster: every arc ending atbnow had a meaning (rather than if somex->bwas meaningless unlessxwas immediately beforeb). - I added a sequence number for each location and added an

AllDifferentconstraint. The sequence number also depended on the arcs; along with theAllDifferent, the number of possible combinations of sequences would limit possibilities, increasing the speed of the sequencing optimizer.

Large Neighborhood Search

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from my previous company, it’s the value of the large neighborhood search. Time and time again I’ve seen it work well for large problems where more traditional ‘one-shot’ approaches would fail.

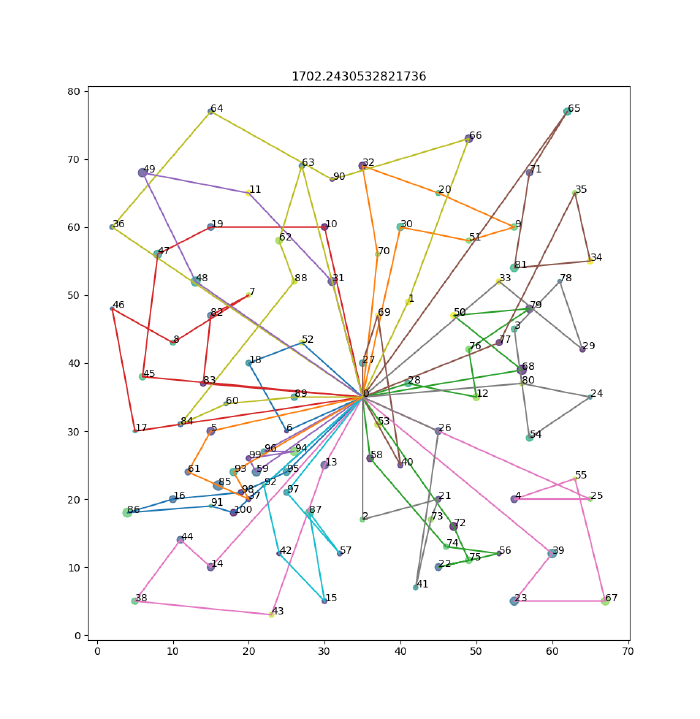

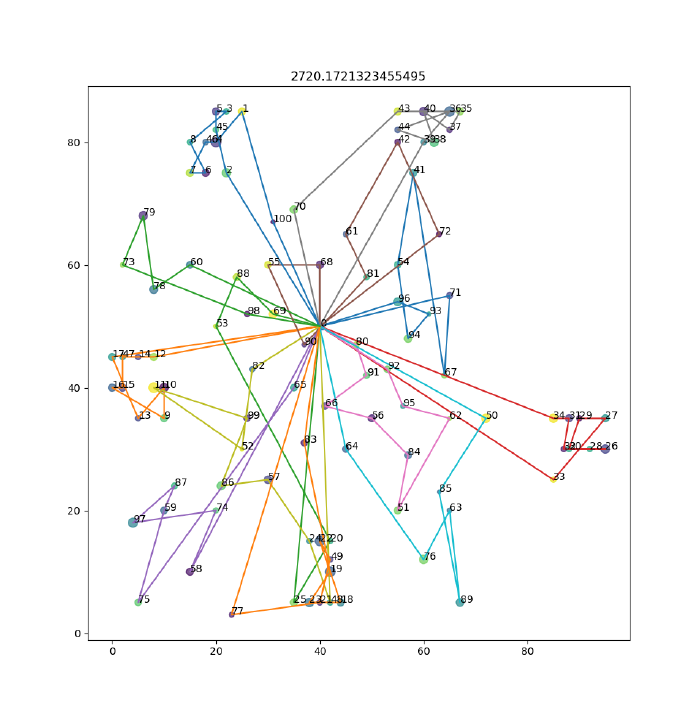

The idea is simple: consider the solution below (a solution for C101). The green truck that goes east from the depot to 90, 88, 76,… does not interact with the red truck that goes west from the depot to 34, 36, 39,…

If the green truck was very badly planned (let’s say it’s taken on too many locations), it would make sense to include only the ’nearby’ trucks in an iteration so that it could more evenly share its load with its neighbors. In this case, the green truck’s neighbors are the cyan (98,96,95,…) and the grey one (80,77,97,…). So the EA would only need to create chromosomes for the locations covered by these three trucks, and it would (hopefully) converge at a locally optimal solution where this part of the solution looks better.

The Large Neighborhood Search might then pick up another truck, let’s say the grey one, and this time it would include it’s neighbors, the green and the brown, thus gradually improving things one neighborhood at a time.

Memoization

Since sequencing was the bottleneck, I wanted to call the sequencing sub-optimizer as few times as possible, and only for new combinations of locations.

Consider a problem where my neighborhood has 5 trucks, and during evolution, some chromosome swaps a location between only two of them. I would not want to re-run the sequencing for the other 3 trucks. Further, I wouldn’t even want to run the sequencing for the two trucks unless the combination were totally ’new’ and I hadn’t seen them in previous iterations.

To do this, I created a dictionary where the keys were tuples of sorted locations and the values were the score.

This brought a tremendous speed improvement (at the cost of memory) to the EA and I highly recommend memoization wherever possible if you’re building an EA yourself.

Concluding thoughts

If you’ve read this far… 🙇🏾♂️

This was quite a fun project to work on. I worked late into the night on Fridays, having lost track of time, which is the best kind of work. All I was doing was looking at text scrolling by in the windows terminal, egging it on… “converge, damn it, converge”…

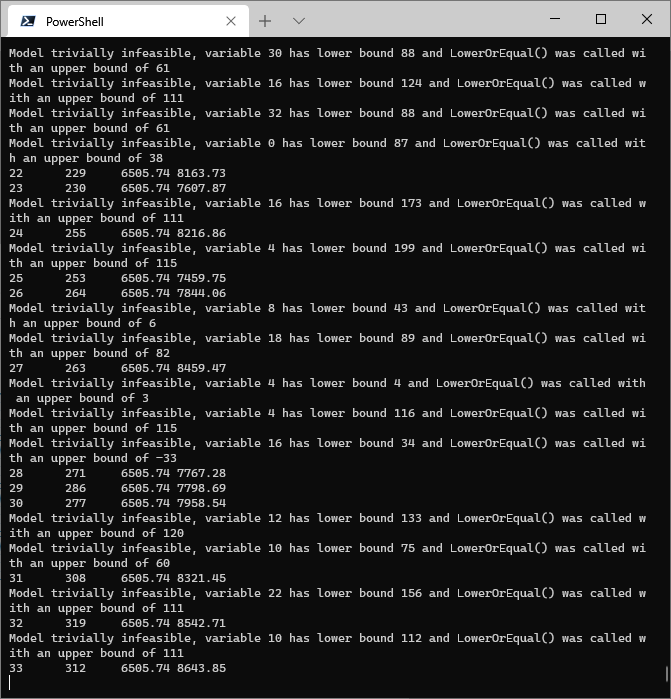

My model NOT converging

Personally I am convinced that with the right hardware, EAs need to be seriously considered, especially for unusual or difficult problems. They are definitely not the solution for every problem: that would be a mistake. To keep costs low, building a library like DEAP (but faster), that is iteratively improved is the right way to go.

A keen reader might have noticed that my results don’t show that EA was able to do what I set out to do when I laid out the context: I wanted to see if EA could do well despite different input data thrown at it. In this case the result for RC101 (this is a dataset with a mix of random and clustered demands) is not good.

I would like to blame it on my own ineptitude rather than the fault of the EA approach. If anything, the DEAP library was quite good in getting me up to speed and getting reasonable results quickly for a first attempt at EAs.